8.3. Bayesian Linear Regression (BLR)#

“La théorie des probabilités n’est que le bon sens réduit au calcul”

(trans.) Probability theory is nothing but common sense reduced to calculation.

—Pierre Simon de Laplace

In this chapter we use Bayes’ theorem to infer a (posterior) probability density function for parameters of a linear statistical model, conditional on data \(\data\). This is called Bayesian linear regression (BLR). In this context “linear” means that the parameters we seek to infer appear in the model only to the first power (specific examples below). You may already be familiar with ordinary (frequentist) linear regression, such as making a least-squares fit of a polynomial to data; later in this chapter we will show how this is related to BLR.

The advantages of doing Bayesian instead of frequentist linear regression are many. The Bayesian approach yields a probability distribution for the unknown parameters and for future model predictions. It also enables us to make all assumptions explicit whereas the frequentist approach puts nearly all emphasis on the collected data. These assumptions can be more general as well; e.g., they allow you to specify prior beliefs on the parameters (such as slope and intercept for a straight line model). Finally, we can do straightforward model checking and add a discrepancy model to account for limitations of the linear model being considered.

We will use BLR to exemplify the general Bayesian workflow we have summarized in Section 2.2 and Section 8.2. To do so, we first need to more precisely define what we mean by linear models.

Background on linear models#

Definition and examples#

In linear modeling the dependence on the model parameters \(\parsLR\) is linear, and this fact will make it possible, for certain priors, to find the distribution of model parameters analytically. Note that we will mostly operate with models depending on more than one parameter. Hence, we denote the model parameters (\(\parsLR\)) using a bold symbol. (We reserve the generic symbol \(\pars\) to include not only \(\parsLR\) but also any other parameters specifying our statistical model.) In this chapter we will, however, consider models (\(\modeloutput\)) that relate a single dependent variable (\(\output\)) with a single independent one (\(\inputt\)).

The linear parameter dependence implies that our model \(\model{\parsLR}{\inputt}\) separates into a sum of parameters times basis functions. Assuming \(N_p\) different basis functions we have

Note that there is no \(\parsLR\)-dependence in the basis functions \(f_j(\inputt)\).

From a machine-learning perspective the different basis functions are known as features.

Example 8.1 (Polynomial basis functions)

A common linear model corresponds to the use of polynomial basis functions \(f_j(x) = x^j\). A polynomial model of degree \(N_p-1\) would then be written

Note that the \(j=0\) basis function is \(f_0(x) = x^0 = 1\) such that the \(\paraLR_0\) parameter becomes the \(x=0\) intercept.

Example 8.2 (Liquid-drop model for nuclear binding energies)

The liquid drop model is useful for a phenomenological description of nuclear binding energies (BE) as a function of the mass number \(A\) and the number of protons \(Z\), neutrons \(N\):

We have five features: the intercept (constant term, bias), the \(A\) dependent volume term, the \(A^{2/3}\) surface term and the Coulomb \(Z^2 A^{-1/3}\) and pairing \((N-Z)^2 A^{-1}\) terms. Although the features are somewhat complicated functions of the independent variables \(A,N,Z\), we note that the \(p=5\) regression parameters \(\parsLR = (a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4)\) enter linearly.

Checkpoint question

Is a Fourier series expansion of a function a linear model?

Hint

If \(f(x)\) is an odd function with period \(2L\), a Fourier sine expansion of \(f(x)\) with \(N\) terms takes the form

where the \(b_n\) are to be determined.

Answer

The parameters \(b_n\) appear linearly, so this is a linear model if only the parameters are being determined (i.e. \(L\) and \(N\) are given). Note that with finite \(N\) this model will not be a perfect reproduction of a general \(f(x)\), so there will be a discrepancy.

Checkpoint question

Which of the following are linear models and which are nonlinear?

Hint

Remember that it is the parameter dependence that dictates whether it is linear.

Answer

The first and third are linear, the second is not (because of the \(b\) parameter).

Converting linear models to matrix form#

When using a linear model we have access to a set of data \(\mathcal{D}\) for the dependent variable, e.g., the \(N_d\) values

For each datum \(y_i\) there is an independent variable \(x_i\), and our model for the \(i^{\text{th}}\) datum is

We can collect the basis functions evaluated at each independent variable \(x_i\) in a matrix \(\mathbf{X}\) of dimension \(N_d \times N_p\):

This matrix will be referred to as a design matrix.

Example 8.3 (The design matrix for polynomial models)

The design matrix for a linear model with polynomial basis functions becomes

where we are considering a polynomial of degree \(p-1\), which implies a model with \(p\) features (including the intercept). It is also known in linear algebra circles as a Vandermonde matrix.

Checkpoint question

What is the design matrix for a Fourier cosine series expansion with \(N_p\) terms (plus a constant)?

Hint

If \(f(x)\) is an even function with period \(2L\), a Fourier cosine expansion of \(f(x)\) with \(N_p\) terms (plus a constant) takes the form

where the \(a_n\) are to be determined.

Answer

For convenience, let \(\omega = \pi/L\). Then the design matrix is:

Next, using the column vector \(\parsLR\) for the parameters,

we can write the general (additive) statistical model

with \(M(\parsLR) \rightarrow M(\parsLR; \inputt)\) as the matrix equation

The last term \(\residuals\) is a column vector of so-called residuals. This term includes both the data uncertainty \(\delta\data\) and the model uncertainty \(\delta M\), i.e., it expresses the part of the dependent variable, for which we have data, that we cannot describe using a linear model. Formally, we can therefore write \(\residual_i = y_i - M_i\) and define the vector \(\residuals\) as

It is important to realize that our model \(M\) provides an approximate description of the data. For now we will take \(\delta M = 0\); that is, we assume that the entire residual is explained by data uncertainty. More generally we expect that \(\delta M \neq 0\) (this is often summarized as all models are wrong) because in a realistic setting we have no guarantee that the data is generated by a linear process. Of course, based on physics insight, or other assumptions, there might exist very good reasons for using a linear model to explain the data (taking into account \(\delta\data\)).

Checkpoint question

Why does the Fourier series from the last section have to be truncated to a finite number of terms in practice?

Hint

Could I do linear algebra with \(N = \infty\)?

Answer

Our manipulations will be with finite matrices, so the basis size must be finite in practice.

The normal equation#

A regression analysis often aims at finding the parameters \(\parsLR\) of a model \(M\) such that the vector of residuals \(\residuals\) is minimized in the sense of its Euclidean norm (or 2-norm). This is assumed in the familiar least-squares analysis. Below we will see that this particular goal arises naturally in Bayesian linear regression.

Here we will lay the groundwork for an analytical solution to the linear regression problem by finding the set of parameters \(\parsLR^*\) (we will typically use an asterisk to denote specific parameters that are “optimal” in some sense) that minimizes

The solution to this optimization problem turns out to be a solution of the normal equation and is known as ordinary least-squares or ordinary linear regression. (Later an exercise will have you generalize this problem to the case where the last factor in Eq. (8.15) has a covariance matrix between the two terms.)

Theorem 8.1 (Ordinary least squares (the normal equation))

The ordinary least-squares method corresponds to finding the optimal parameter vector \(\parsLR^*\) that minimizes the Euclidean norm of the residual vector \(\residuals = \data - \dmat \parsLR\), where \(\data\) is a column vector of observations and \(\dmat\) is the design matrix (8.8).

Finding this optimum turns out to correspond to solving the normal equation

Given that the normal matrix \(\dmat^T\dmat\) is invertible, the solution to the normal equation is given by

Proof. Due to its quadratic form, the Euclidean norm \(\left| \residuals \right|_2^2 = \left(\data-\dmat\parsLR\right)^T\left(\data-\dmat\parsLR\right) \equiv C(\parsLR)\) is bounded from below and we just need to find the single extremum. That is we need to solve the problem

In practical terms it means we will require

where \(y_i\) and \(f_j(x_i)\) are the elements of \(\data\) and \(\dmat\), respectively. Performing the derivative results in

which is one element of the full gradient vector. This gradient vector can be succinctly expressed in matrix-vector form as

The minimum of \(C\), where \(\boldsymbol{\nabla}_{\parsLR} C(\parsLR) = 0\), then corresponds to

which is the normal equation. Finally, if the matrix \(\dmat^T\dmat\) is invertible then we have the solution

The pseudo-inverse (or Moore-Penrose inverse)

We note that since our design matrix is defined as \(\dmat\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N_d\times N_p}\), the combination \(\dmat^T\dmat \in {\mathbb{R}}^{N_p\times N_p}\) is a square matrix. The product \(\left(\dmat^T\dmat\right)^{-1}\dmat^T\) is called the pseudo-inverse of the design matrix \(\dmat\). The pseudo-inverse is a generalization of the usual matrix inverse. The former can be defined also for non-square matrices that are not necessarily full rank. In the case of full-rank and square matrices the pseudo-inverse is equal to the usual inverse.

Spot the error!

Your classmate simplifies \(\dmat^T\data = \dmat^T\dmat\parsLR^*\) as \(\data = \dmat\parsLR^*\) and then solves for \(\parsLR^*\) as \(\parsLR^* = \dmat^{-1}\data\). What is wrong?

Answer

\(\dmat\) is not a square matrix (in general).

The regression residuals \(\residuals^{*} = \data - \dmat \parsLR^{*}\) can be used to obtain an estimator \(s^2\) of the variance of the residuals

where \(N_p\) is the number of parameters in the model and \(N_d\) is the number of data.

In frequentist linear regression using the ordinary least-squares method we make a leap of faith and decide that we are seeking a “best” model with an optimal set of parameters \(\parsLR^*\) that minimizes the Euclidean norm of the residual vector \(\residuals\), as above.

Workflow for Bayesian linear regression#

In following the four-step workflow for Bayesian inference (see Section 2.2), we need to

Identify the observable and unobservable quantities and formulate appropriately informative priors before new data is used.

Set up a full statistical model relating the physics model and data, including all errors. We need to consistently build in our knowledge of the underlying physics and of the data measurement process.

Calculate and interpret the relevant posterior distributions. This is the conditional probability distribution of the unobserved quantities of interest, given the observed data.

Do model checking: assess the fit of the model and the reasonableness of the conclusions, testing the sensitivity to model assumptions in steps 1 and 2. From this assessment we modify the model appropriately and repeat all four steps.

To carry out this workflow for BLR, we note that our goal is to relate data \(\data\) to the output of a linear model expressed in terms of its design matrix \(\dmat\) and its model parameters \(\parsLR\) by \(M = \dmat \parsLR\). We consider the special case of one dependent response variable (\(\output\)) and a single independent variable (\(\inputt\)), for which the data set (\(\data\)) and the residual vector (\(\residuals\)) are both \(N_d \times 1\) column vectors with \(N_d\) the length of the data set. The design matrix (\(\dmat\)) has dimension \(N_d \times N_p\) and the parameter vector (\(\parsLR\)) is \(N_p \times 1\).

For the residuals, consider a statistical model that describes the mismatch between our model and observations as in Eq. (8.12) (recall that we assume here that \(\delta M = 0\)). Knowledge (and/or assumptions) concerning measurement uncertainties, or modeling errors, then allows to describe the residuals as a vector of random variables that are distributed according to a PDF

where we introduce the relation \(\sim\) to indicate how a (random) variable is distributed. A very common assumption is that errors are normally distributed with zero mean. As before we let \(N_d\) denote the number of data points in the (column) vector \(\data\). Introducing the \(N_d \times N_d\) covariance matrix \(\covres\) for the errors we then have the explicit distribution

Recall that the notation for the multivariate normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}\) here is that the mean is \(\zeros\) and the covariance matrix is \(\covres\).

To carry out step 2. we adapt Bayes’ theorem to the current problem

which is the conditioned probability of the quantities of interest, namely the model parameters, on the observed measurements with known covariance for the measurement errors. In most realistic data analyses we will then have to resort to numerical evaluation or sampling of the posterior. However, certain combinations of likelihoods and priors facilitate analytical derivation of the posterior. In this chapter we will explore one such situation and also demonstrate how we can recover the results from an ordinary least squares approach with certain assumptions. A slightly more general approach involves so called conjugate priors. This class of probability distributions have clever functional relationships with corresponding likelihood distributions that facilitate analytical derivation.

To evaluate this posterior we must have expressions for both factors in the numerator on the right-hand side (following the Bayesian research workflow in Section 8.2): the prior \(\pdf{\parsLR}{I}\) and the likelihood \(\pdf{\data}{\parsLR,\covres,I}\). Note that the prior does not depend on the data or the error model. The denominator \(\pdf{\data}{I}\), sometimes known as the evidence, becomes irrelevant for the task of parameter estimation since it does not depend on \(\parsLR\). It is typically quite challenging, if not impossible, to evaluate the evidence for a multivariate inference problem except for some very special cases. In this chapter we will only be dealing with analytically tractable problems and will therefore (in principle) be able to evaluate also the evidence.

Checkpoint question

Why is it possible to perform parameter estimation without computing the evidence?

Hint

In Bayes theorem, the posterior is normalized. Verify this by integrating both sides over the parameters. For parameter estimation, do you need the posterior to be normalized (e.g., do you need more than the shape and location of the posterior density)?

Checkpoint question

Can you think of why it is so challenging to compute the evidence?

Hint

To evaluate the evidence, you need to introduce an integral over all possible values of \(\pars\). Why might this integral harder to do than the likelihood or prior evaluation?

The prior#

First we assign a prior probability \(\pdf{\parsLR}{I}\) for the model parameters. In order to facilitate analytical expressions we will explore two options: (i) a very broad, uniform prior, and (ii) a Gaussian prior. For simplicity, we consider both these priors to have zero mean and with all model parameters being i.i.d.

As discussed earlier, we rarely want to use a truly uniform prior, preferring a wide beta or Gaussian distribution instead. We will assume that the width is large enough that it will be effectively flat where our Bayesian linear regression likelihood is not negligible. Then for the analytic calculations here we can take the uniform prior for the \(N_p\) parameters to be

with \(\Delta\paraLR\) the width of the prior range in all parameter directions (this assumes we have standardized the data so that it has roughly the same extent in all directions).

The Gaussian prior that we will also be exploring is

with \(\sigma_\paraLR\) the standard deviation of the prior for all parameters.

Checkpoint question

Are these priors normalized?

Hint-1

Integrate both sides over \(\parsLR\) to check normalization, remembering that \(\parsLR\) is a vector, so this is a multidimensional integral.

Hint-2

Both normalization integrals in this case can be factorized into the product of one-dimensional integrals. This is true here for the Gaussian prior because the covariance matrix is taken to be diagonal.

Answer

Yes, they are normalized.

Checkpoint question

In what limit are the uniform and Gaussian priors (as defined here) effectively equivalent?

Answer

The limit where \(\Delta\paraLR/2\) and \(\sigma_\paraLR\) are both so large that the priors are effectively flat where the likelihood is not negligible.

Checkpoint question

What is implied (i.e., what are you assuming) if you use a truly uniform prior for model parameters?

Hint

Is it possible that the parameters could be arbitrarily large?

Answer

It is implied that not only is any magnitude possible for the model parameters, but all values for a given parameter are equally likely. This is very unlikely to be true.

The likelihood#

Assuming normally distributed residuals, as we have done, it turns out to be straightforward to express the data likelihood. In the following we will make the further assumption that errors are independent. This implies that the covariance matrix \(\covres\) is diagonal and given by a vector \(\sigmas\),

and \(\sigmai^2\) is the variance for residual \(\residual_i\).

Let’s first consider a single datum \(\data_i\) and the corresponding model prediction \(M_i = \left( \dmat \parsLR \right)_i\). We are interested in the likelihood for this single data point

Since the relation between data and residual is a simple additive transformation \(\data_i = \modeloutput_i + \residual_i\), we can use the standard probability rules to obtain (alternatively we can apply the recipe for changing variables (add reference))

where we used that \(\residual_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigmai^2)\). Note that the parameter dependence sits in \(\modeloutput_i \equiv \modeloutput(\parsLR, \inputs_i)\).

Checkpoint question

Fill in the details for the steps in (8.32).

Hint

Review the probability rules in Chapter 4. The first step integrates in \(\residual_i\).

Answer

Apply the sum rule to integrate in \(\residual_i\).

Apply the product rule, taking into account that \(\residual_i\) depends only on \(\sigmai\).

Use \(\data_i = \modeloutput_i + \residual_i\) to evaluate the first pdf; it is a \(\delta\) function because \(\data_i\) is exactly specified given \(\modeloutput_i \equiv \modeloutput(\parsLR, \inputs_i)\) and \(\epsilon_i\).

Evaluate the integral using the \(\delta\) function and \(\delta\bigl(\data_i - (\modeloutput_i + \residual_i)\bigr) = \delta\bigl(\epsilon_i - (\data_i - \modeloutput_i)\bigr)\).

Furthermore, since we assume that the residuals are independent we find that the total likelihood becomes a product of the individual ones for each element of \(\data\):

where we note that the diagonal form of \(\covres\) implies that \(\left| \covres \right|^{1/2} = \prod_{i=0}^{N_d-1} \sigmai\) and that the exponent becomes a sum of squared and weighted residual terms

In the special case that all residuals are both independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) we have that all variances are the same, \(\sigmai^2 = \sigmares^2\), and the full covariance matrix is completely specified by a single parameter \(\sigmares^2\). For this special case, the likelihood becomes

Caution

For computational performance it is always better (if possible) to write sums, such as the one in the exponent of (8.35), in the form of vector-matrix operations rather than as for-loops. This particular sum should therefore be implemented as \((\data - \dmat \parsLR)^T (\data - \dmat \parsLR)\) to employ powerful optimization for vectorized operations in existing numerical libraries (such as numpy in python and gsl, mkl for C and other compiled programming languages).

Two views on the likelihood

Since observed data is generated stochastically, through an underlying \(\text{``data-generating process''}\), it is appropriately described by a probabibility distribution. This is the \(\text{``data likelihood''}\) that describes the probability distribution for observed data given a specific data-generating process (as indicated by the information on the right-hand side of the conditional).

View 1: Assuming fixed values of \(\parsLR\); what are long-term frequencies of future data observations as described by the likelihood?

View 2: Focusing on the data \(\data_\mathrm{obs}\) that we have; how does the likelihood for this data set depend on the values of the model parameters?

This second view is the one that we will be adopting when allowing model parameters to be associated with probability distributions. The likelihood still describes the probability for observing a set of data, but we emphasize its parameter dependence by writing

This function is not a probability distribution for model parameters. The parameter posterior, left-hand side of Eq. (8.27), regains status as a probability density for \(\parsLR\) since the likelihood is multiplied with the prior \(\pdf{\parsLR}{I}\) and normalized by the evidence \(\pdf{\data}{I}\).

The posterior#

Given the likelihood with i.i.d. errors (8.35) and the two alternative priors, (8.28) and (8.29), we will derive the corresponding two different expressions for the posterior (up to multiplicative normalization constants).

Rewriting the likelihood#

First, let us rewrite the likelihood in a way that is made possible by the fact that we are considering a linear model. In particular, this implies quadratic dependence on model parameters in the exponent, which means one can show (by performing a Taylor expansion of the log likelihood around the mode) that the likelihood becomes proportional to the functional form of a multivariate normal distribution for the model parameters:

Note that this expression still describes a probability distribution for the data. The data dependence sits in the amplitude of the mode, \(\pdf{\data}{\optparsLR,\sigmares^2,I}\), and its position, \(\optparsLR = \optparsLR(\data) = \left(\dmat^T\dmat\right)^{-1}\dmat^T\data\). The latter is the solution (8.17) of the normal equation when the covariance matrix is proportional to the identity: \(\covres = \mathrm{diag}(\sigmares^2)\). Furthermore, the statistical model for the errors in this case enter in the covariance matrix,

which can be understood as the curvature (Hessian) of the negative log-likelihood.

Exercise 8.1 (Prove the Gaussian likelihood)

Prove Eq. (8.37).

Hints

Identify \(\optparsLR\) as the position of the mode of the likelihood by inspecting the negative log-likelihood \(L(\parsLR)\) and comparing with the derivation of the normal equation.

Taylor expand \(L(\parsLR)\) around \(\optparsLR\). For this you need to argue (or show) that the gradient vector \(\nabla_{\parsLR} L(\parsLR) = 0\) at \(\pars=\optparsLR\), and show that the Hessian \(\boldsymbol{H}\) (with elements \(H_{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 L}{\partial\paraLR_i\partial\paraLR_j}\)) is a constant matrix \(\boldsymbol{H} = \frac{\dmat^T\dmat}{\sigmares^2}\).

Compare with the Taylor expansion of a normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}\left( \parsLR \vert \optparsLR, \covparsLR \right)\).

Exercise 8.2 (Generalized normal equation)

Prove for the case of the general exponent in Eq. (8.33) that the position of the mode \(\optparsLR\) is given by

Checkpoint question

Why can’t I say \( \bigl[\dmat^T \covres^{-1} \dmat\bigr]^{-1} \bigl[\dmat^T \covres^{-1} \data\bigr] = \dmat^{-1} \covres (\dmat^T)^{-1} \dmat^T \covres^{-1} \data = \dmat^{-1}\data\)?

Answer

Because these are not square, invertible matrices, so those operations don’t hold.

Posterior with a uniform prior#

Let us first consider a uniform prior as expressed in Eq. (8.28). The prior can be considered very broad if its boundaries \(\pm \Delta\para/2\) are very far from the mode of the likelihood (8.37). “Distance” in this context is measured in terms of standard deviations. A “far distance”, therefore, implies that \(\pdf{\data}{\parsLR,\sigmares^2,I}\) is very close to zero. This implies that the posterior

simply becomes proportional to the data likelihood (with the prior just truncating the distribution at very large distances). Thus we find from Eq. (8.37)

if all \(\paraLR_i \in [-\Delta\paraLR/2, +\Delta\paraLR/2]\) while it is zero elsewhere. The mode of this distribution is obviously the mean vector \(\optparsLR = \optparsLR(\data)\). We can therefore say that we have recovered the ordinary least-squares result. At this stage, however, the interpretation is that this parameter optimum corresponds to the maximum of the posterior PDF (8.40). Such an optimum is sometimes known as the maximum a posteriori, or MAP.

Checkpoint question

Why is it obvious that the mode of \(\pdf{\parsLR}{\data,\sigmares^2,I}\) is the mean vector \(\optparsLR\)?

Answer

The argument of the exponent is negative semi-definite, so the mode (maximum value) of the distribution is when the exponent is equal to zero, which is when \(\parsLR = \optparsLR\).

Discuss

In light of the results of this section, what assumption(s) are implicit in linear regression while they are made explicit in Bayesian linear regression?

Posterior with a Gaussian prior#

Assigning instead a Gaussian prior for the model parameters, as expressed in Eq. (8.29), we find that the posterior is proportional to the product of two exponential functions

The second proportionality is a consequence of both exponents being quadratic in the model parameters, and therefore that the full expression looks like the product of two Gaussians. This product is proportional to another Gaussian distribution which has mean vector and (inverse) covariance matrix given by

where \(\boldsymbol{1}\) is the \(N_p \times N_p\) unit matrix. In effect, what has happend is that the prior normal distribution becomes updated to a posterior normal distribution via an inference process that involves a data likelihood. In this particular case, learning from data implies that the mode changes from \(\parsLR\) to \(\tilde{\parsLR}\) and the covariance from a diagonal structure with \(\sigma_{\paraLR}^2\) in all directions to the covariance matrix \(\tildecovparsLR\).

Checkpoint question

What happens if the data is of high quality (i.e., the likelihood \(\mathcal{L}(\parsLR)\) is sharply peaked around \(\optparsLR\)), and what happens if it is of poor quality (providing a very broad likelihood distribution)?

Marginal posterior distributions#

Given a multivariate probability distribution we are often interested in lower dimensional marginal distributions. Consider for example \(\parsLR^T = [\parsLR_1^T, \parsLR_2^T\)], that is partitioned into dimensions \(D_1\) and \(D_2\). The marginal distribution for \(\parsLR_2\) corresponds to the integral

Transformation property of multivariate normal distributions

Let \(\mathbf{Y}\) be a multivariate normal-distributed random variable of length \(N_p\) with mean vector \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) and covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\). We use the notation \(\psub{\mathbf{Y}}{\mathbf{y}} = \mathcal{N} (\mathbf{y} | \mathbf{\mu}, \mathbf{\Sigma})\) to emphasize which variable is normally distributed.

Consider now a general \(N_p \times N_p\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\) and \(N_p \times 1\) vector \(\boldsymbol{b}\). Then, the random variable \(\mathbf{Z} = \boldsymbol{A} \mathbf{Y} + \boldsymbol{b}\) is also multivariate normal-distributed with the PDF

For multivariate normal distributions we can employ a useful transformation property, shown in Eq. (8.43). Considering the posterior (8.41) we partition the parameters \(\parsLR^T = [\parsLR_1^T, \parsLR_2^T\)] and the mean vector and covariance matrix into \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^T = [\boldsymbol{\mu}_1^T,\boldsymbol{\mu}_2^T]\) and

We can obtain the marginal distribution for \(\parsLR_2\) by setting

which yields

The posterior predictive#

One can also derive the posterior predictive distribution (PPD), i.e., the probability distribution for predictions \(\widetilde{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}}\) given the model \(M\) and a set of new inputs for the independent variable \(\boldsymbol{x}\). The new inputs give rise to a new design matrix \(\widetilde{\dmat}\).

We obtain the posterior predictive distribution by marginalizing over the uncertain model parameters that we just inferred from the given data \(\data\).

where both distributions in the integrand can be expressed as Gaussians. Alternatively, one can express the PPD as the set of model predictions with the model parameters distributed according to the posterior parameter PDF

This set of predictions can be obtained if we have access to a set of samples from the parameter posterior.

Checkpoint question

Fill in the details to obtain the right side of (8.45).

Answer

Introduce the integration over \(\parsLR\) using the sum rule and then obtain the right side from the product rule.

Bayesian linear regression: warmup#

Prelude: ordinary linear regression#

To warm up, and get acquainted with the notation and formalism, let us work out a small example. Assume that we have the situation where we have collected two datapoints \(\data = [y_1,y_2]^T = [-3,3]^T\) for the predictor values \([x_1,x_2]^T = [-2,1]^T\).

This data could have come from any process, even a non-linear one. But this is artificial data that I generated by evaluating the function \(y = 1 + 2x\) at \(x=x_1=-2\) and \(x=x_2=1\). Clearly, the data-generating mechanism is very simple and corresponds to a linear model \(y = \paraLR_0 + \paraLR_1 x\) with \([\paraLR_0,\paraLR_1] = [1,2]\). This is the kind of information we never have in reality. Indeed, we are always uncertain about the process that maps input to output, and as such our model \(M\) will always be wrong. We are also uncertain about the parameters \(\parsLR\) of our model. These are the some of the fundamental reasons for why it can be useful to operate with a Bayesian approach where we can assign probabilities to any quantity and statement. In this example, however, we will continue with the standard (frequentist) approach based on finding the parameters that minimize the squared errors (i.e., the norm of the residual vector).

We will now assume a linear model with polynomial basis up to order one to model the data, i.e.,

which we can express in terms of a design matrix \(\dmat\) and (unknown) parameter vector \(\parsLR\) as \(M = \dmat \parsLR\).

In the present case the two unknowns \(\parsLR = [\paraLR_0,\paraLR_1]^T\) can be fit to the two datapoints \(\data = [-3,3]^T\) using pen a paper.

Exercise 8.3

In the example above you have two data points and two unknowns, which means you can easily solve for the model parameters using a conventional matrix inverse. Do the numerical calculation to make sure you have set up the problem correctly.

Exercise 8.4

Evaluate the normal equations for the design matrix \(\dmat\) and data vector \(\data\) in the example above.

Exercise 8.5

Evaluate the sample variance \(s^2\) for the example above using Eq. (8.24). Do you think the result makes sense?

Continuing …#

For the time being we assume to know enough about the data to consider a normal likelihood with i.i.d. errors. Let us first set the known residual variance to \(\sigmares^2 = 0.5^2\).

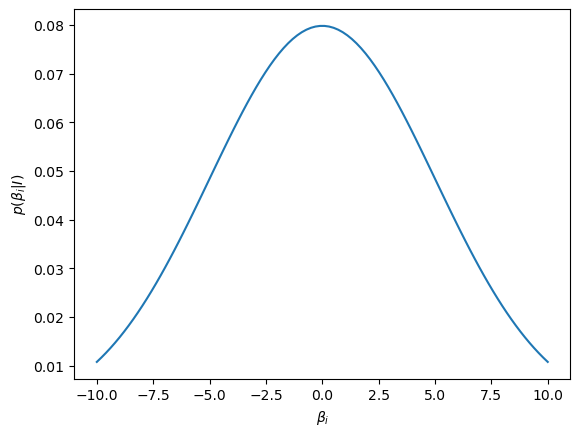

This time we also have prior knowledge that we would like to build into the inference. Here we use a normal prior for the parameters with \(\sigma_\paraLR = 5.0\), which is to say that before looking at the data we believe the pdf for \(\parsLR\) to be centered on zero with a variance of \(5^2\).

Let us plot this prior. The prior is the same for \(\paraLR_0\) and \(\paraLR_1\), so it is enough to plot one of them.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.stats import norm

def normal_distribution(mu,sigma2):

return norm(loc=mu,scale=np.sqrt(sigma2))

betai = np.linspace(-10,10,100)

prior = normal_distribution(0,5.0**2)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,1)

ax.plot(betai,prior.pdf(betai))

ax.set_ylabel(r'$p(\beta_i \vert I )$')

ax.set_xlabel(r'$\beta_i$');

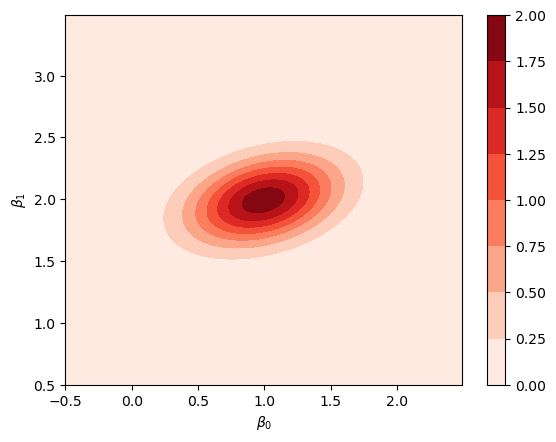

It is straightforward to evaluate Eq. (8.42), which gives us

This should be compared with the parameter vector \((1,2)\) we recovered using ordinary linear regression. With Bayesian linear regression we start from an informative prior with both parameters centered on zero with a rather large variance.

Exercise 8.6 (Warm-up Bayesian linear regression)

Reproduce the posterior mean and covariance matrix from Eq. (8.47). You can use numpy methods to perform the linear algebra operations.

We can plot the posterior probability distribution for \(\pars\), i.e., by plotting the bi-variate \(\mathcal{N}-\)distribution with the parameter in Eq. (8.47).

from scipy.stats import multivariate_normal

mu = np.array([0.992,1.992])

Sigma = np.linalg.inv(4 * np.array([[2.01,-1.0],[-1.0,5.01]]))

posterior = multivariate_normal(mean=mu, cov=Sigma)

beta0, beta1 = np.mgrid[-0.5:2.5:.01, 0.5:3.5:.01]

beta_grid = np.dstack((beta0, beta1))

fig,ax = plt.subplots(1,1)

ax.set_xlabel(r'$\beta_0$')

ax.set_ylabel(r'$\beta_1$')

im = ax.contourf(beta0, beta1, posterior.pdf(beta_grid),cmap=plt.cm.Reds);

fig.colorbar(im);

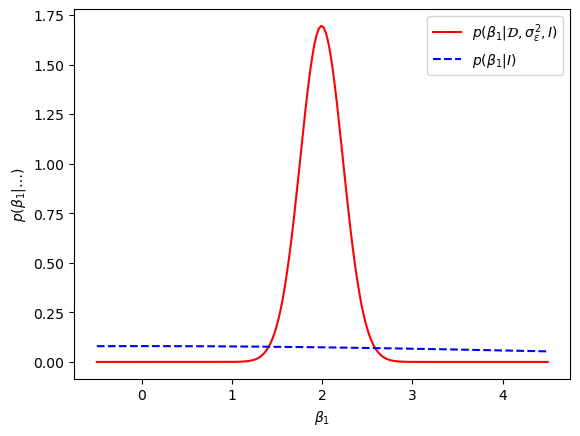

Using Eq. (8.44) we can obtain, e.g., the \(\paraLR_1\) marginal density and compare with the prior

beta1 = np.linspace(-0.5,4.5,200)

mu1 = mu[1]

Sigma11_sq = Sigma[1,1]

posterior1 = normal_distribution(mu1,Sigma11_sq)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,1)

ax.plot(beta1,posterior1.pdf(beta1),'r-',\

label=r'$p(\beta_1 \vert \mathcal{D}, \sigma_\epsilon^2, I )$')

ax.plot(beta1,prior.pdf(beta1), 'b--',label=r'$p(\beta_1 \vert I )$')

ax.set_ylabel(r'$p(\beta_1 \vert \ldots )$')

ax.set_xlabel(r'$\beta_1$')

ax.legend(loc='best');

The key take-away with this numerical exercise is that Bayesian inference yields a probability distribution for the model parameters whose values we are uncertain about. With ordinary linear regression techniques you only obtain the parameter values that optimize some cost function, and not a probability distribution.

Exercise 8.7 (Warm-up Bayesian linear regression (data errors))

Explore the sensitivity to changes in the residual errors \(\sigmares\). Try to increase and reduce the error.

Exercise 8.8 (Warm-up Bayesian linear regression (prior sensitivity))

Explore the sensitivity to changes in the Gaussian prior width \(\sigma_\paraLR\). Try to increase and reduce the width.

Exercise 8.9 (“In practice” Bayesian linear regression)

Perform Bayesian Linear Regression on the data that was generated in Addendum: Ordinary linear regression in practice. Explore:

Dependence on the quality of the data (generate data with different \(\sigma_\epsilon\)) or the number of data.

Dependence on the polynomial function that was used to generate the data.

Dependence on the number of polynomial terms in the model.

Dependence on the parameter prior.

In all cases you should compare the Bayesian inference with the results from Ordinary Least Squares and with the true parameters that were used to generate the data.

Solutions to selected exercises#

Solution to

The likelihood can be written \(\pdf{\data}{\parsLR,I} = \exp\left[ -L(\parsLR) \right]\), where we include information on the error distribution (\(\sigmares\)) in the conditional \(I\). The negative log-likelihood, including the normalization factor, is

Comparing with Eq. (8.15) and the corresponding gradient vector (8.21) we find that

\[ \nabla_{\pars} L(\parsLR) = -\frac{\dmat^T\left( \data-\dmat\pars\right)}{\sigmares^2}, \]which is zero at \(\pars = \optparsLR = \left(\dmat^T\dmat\right)^{-1}\dmat^T\data\) corresponding to the solution of the normal equation.

We can Taylor expand \(L(\parsLR)\) around \(\parsLR=\optparsLR\) realizing that the linear (gradient) term is zero. Furthermore, the quadrating term depends on the second derivative (hessian) which is a constant matrix since \(L\) only depends quadratically on the parameters

Since higher derivatives therefore must be zero, the Taylor expansion actually terminates at second order

We introduce \(\covparsLR^{-1} \equiv {\dmat^T\dmat} / {\sigmares^2}\) and use that \(\exp\left[ - L(\optparsLR) \right] = \pdf{\data}{\optparsLR,I}\). Therefore, evaluating \(\exp\left[ -L(\parsLR) \right]\) gives

\[ \pdf{\data}{\parsLR,I} = \pdf{\data}{\optparsLR,I} \exp\left[ -\frac{1}{2} (\pars-\optparsLR)^T \covparsLR^{-1} (\pars-\optparsLR) \right], \]as we wanted to show.

Solution to

We have the following design matrix

which in the present case yields the parameter values

Solution to

For the warmup case we have fitted a straight line through two data points, which is always possible, and we cannot determine the sample variance. This will be even more clear when we come to Bayesian Linear Regression (BLR).

Addendum: Ordinary linear regression in practice#

We often have situation where we have much more than just two datapoints, and they rarely fall exactly on a straight line. Let’s use python to generate some more realistic, yet artificial, data. Using the function below you can generate data from some linear process with random variables for the underlying parameters. We call this a data-generating process.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def data_generating_process_reality(model_type, rng=np.random.default_rng(), **kwargs):

if model_type == 'polynomial':

true_params = rng.uniform(low=-5.0, high=5, size=(kwargs['poldeg']+1,))

#polynomial model

def process(params, xdata):

ydata = np.polynomial.polynomial.polyval(xdata,params)

return ydata

# use this to define a non-polynomial (possibly non-linear) data-generating process

elif model_type == 'nonlinear':

true_params = None

def process(params, xdata):

ydata = (0.5 + np.tan(np.pi*xdata))**2

return ydata

else:

print(f'Unknown Model')

# return function for the true process the values for the true parameters

# and the name of the model_type

return process, true_params, model_type

Next, we make some measurements of this process, and that typically entails some measurement errors. We will here assume that independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.) measurement errors \(e_i\) that all follow a normal distribution with zero mean and variance \(\sigma_e^2\). In a statistical notation we write \(e_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma_e^2)\). By default, we set \(\sigma_e = 0.5\).

def data_generating_process_measurement(process, params, xdata,

sigma_error=0.5, rng=np.random.default_rng()):

ydata = process(params, xdata)

# sigma_error: measurement error.

error = rng.normal(0,sigma_error,len(xdata)).reshape(-1,1)

return ydata+error, sigma_error*np.ones(len(xdata)).reshape(-1,)

Let us setup the data-generating process, in this case a linear process of polynomial degree 1, and decide how many measurements we make (\(N_d=10\)). All relevant output is stored in pandas dataframes.

#the number of data points to collect

# -----

Nd = 10

# -----

# predictor values

xmin = -1 ; xmax = +1

Xmeasurement = np.linspace(xmin,xmax,Nd).reshape(-1,1)

# store it in a pandas dataframe

pd_Xmeasurement = pd.DataFrame(Xmeasurement, columns=['x'])

# Define the data-generating process.

# Begin with a polynomial (poldeg=1) model_type

# in a second run of this notebook you can play with other linear models

reality, true_params, model_type = data_generating_process_reality(model_type='polynomial',poldeg=1)

print(f'model type : {model_type}')

print(f'true parameters : {true_params}')

print(f'Nd = {Nd}')

# Collect measured data

# -----

sigma_e = 0.5

# -----

Ydata, Yerror = data_generating_process_measurement(reality,true_params,Xmeasurement,sigma_error=sigma_e)

# store the data in a pandas dataframe

pd_D=pd.DataFrame(Ydata,columns=['data'])

#

pd_D['x'] = Xmeasurement

pd_D['e'] = Yerror

# We will also produce a denser grid for predictions with our model and comparison with the true process. This is useful for plotting

xreality = np.linspace(xmin,xmax,200).reshape(-1,1)

pd_R = pd.DataFrame(reality(true_params,xreality), columns=['data'])

pd_R['x'] = xreality

model type : polynomial

true parameters : [ 2.1760689 -1.14561434]

Nd = 10

Create some analysis tool to inspect the data, and later on the model.

# helper function to plot data, reality, and model (pd_M)

def plot_data(pd_D, pd_R, pd_M, with_errorbars = True):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(8,6))

ax.scatter(pd_D['x'],pd_D['data'],label=r'Data',color='black',zorder=1, alpha=0.9,s=70,marker="d");

if with_errorbars:

ax.errorbar(pd_D['x'],pd_D['data'], pd_D['e'],fmt='o', ms=0, color='black');

if pd_R is not None:

ax.plot(pd_R['x'], pd_R['data'],color='red', linestyle='--',lw=3,label='Reality',zorder=10)

if pd_M is not None:

ax.plot(pd_M['x'], pd_M['data'],color='blue', linestyle='--',lw=3,label='Model',zorder=11)

ax.legend();

ax.set_title('Collected data');

ax.set_xlabel(r'Predictor $x$');

ax.set_ylabel(r'Response $y$');

return fig,ax

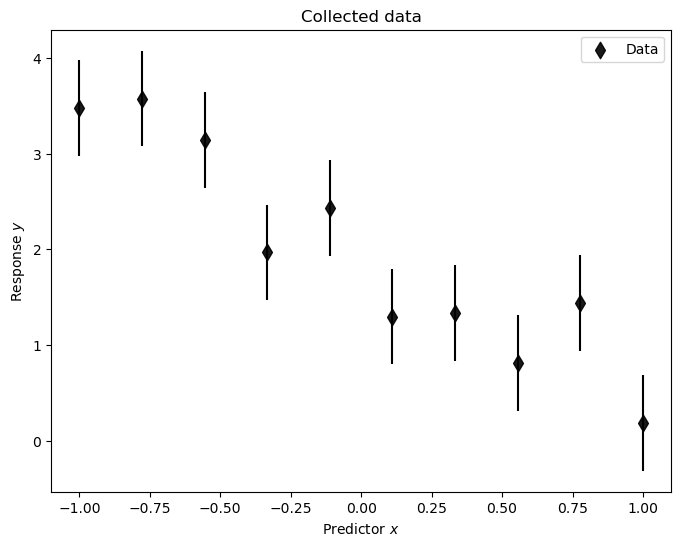

Let’s have a look at the data. We set the last two arguments to None for visualizing only the data.

plot_data(pd_D, None, None);

Linear regression proceeds via the design matrix. We will analyze this data using a linear polynomial model of order 1. The following code will allow you to setup the corresponding design matrix \(\dmat\) for any polynomial order (referred to as poldeg below)

def setup_polynomial_design_matrix(data_frame, poldeg, drop_constant=False, verbose=True):

if verbose:

print('setting up design matrix:')

print(' len(data):', len(data_frame.index))

# for polynomial models: x^0, x^1, x^2, ..., x^p

# use numpy increasing vandermonde matrix

print(' model poldeg:',poldeg)

predictors = np.vander(data_frame['x'].to_numpy(), poldeg+1, increasing = True)

if drop_constant:

predictors = np.delete(predictors, 0, 1)

if verbose:

print(' dropping constant term')

pd_design_matrix = pd.DataFrame(predictors)

return pd_design_matrix

So, let’s setup the design matrix for a model with polynomial basis functions. Note that there are \(N_p\) parameters in a polynomial function of order \(N_p-1\)

Np=2

pd_X = setup_polynomial_design_matrix(pd_Xmeasurement,poldeg=Np-1)

setting up design matrix:

len(data): 10

model poldeg: 1

We can now perform linear regression, or ordinary least squares (OLS), as

#ols estimator for physical parameter theta

D = pd_D['data'].to_numpy()

X = pd_X.to_numpy()

ols_cov = np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X.T,X))

ols_xTd = np.matmul(X.T,D)

ols_theta = np.matmul(ols_cov,ols_xTd)

print(f'Ndata = {Nd}')

print(f'theta_ols \t{ols_theta}')

print(f'theta_true \t{true_params}\n')

Ndata = 10

theta_ols [ 1.96660071 -1.61552068]

theta_true [ 2.1760689 -1.14561434]

To evaluate the (fitted) model we setup a design matrix that spans dense values across the relevant range of predictors.

pd_Xreality = setup_polynomial_design_matrix(pd_R,poldeg=Np-1)

setting up design matrix:

len(data): 200

model poldeg: 1

and then we dot this with the fitted (ols) parameter values

Xreality = pd_Xreality.to_numpy()

pd_M_ols = pd.DataFrame(np.matmul(Xreality,ols_theta),columns=['data'])

pd_M_ols['x'] = xreality

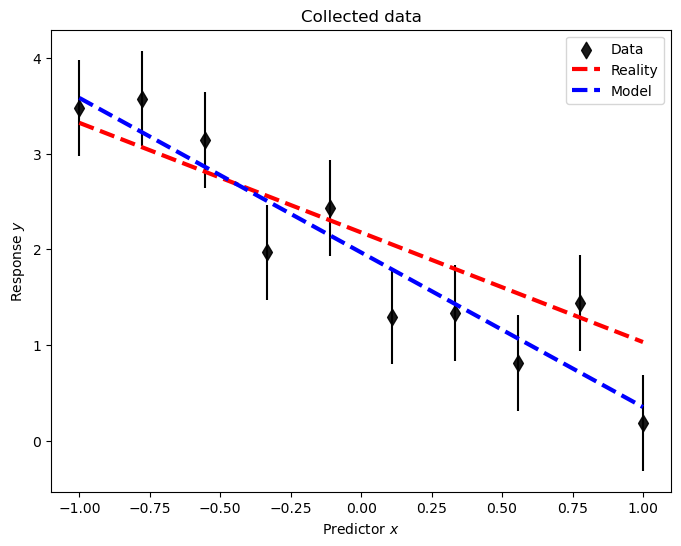

A plot (which now includes the data-generating process ‘reality’) demonstrates the quality of the inference.

plot_data(pd_D, pd_R, pd_M_ols);

To conclude, we also compute the sample variance \(s^2\)

ols_D = np.matmul(X,ols_theta)

ols_eps = (ols_D - D)

ols_s2 = (np.dot(ols_eps,ols_eps.T)/(Nd-Np))

print(f's^2 \t{ols_s2:.3f}')

print(f'sigma_e^2 \t{sigma_e**2:.3f}')

s^2 0.183

sigma_e^2 0.250

As seen, the extracted variance is in some agreement with the true one.

Using the code above, you should now try to do the following exercises.

Exercise 8.10

Keep working with the simple polynomial model \(M = \paraLR_0 + \paraLR_1 x\)

Reduce the number of data to 2, i.e., set Nd=2. Do you reproduce the result from the simple example in the previous section?

Increase the number of data to 1000. Do the OLS values of the model parameters and the sample variance approach the (true) parameters of the data-generating process? Is this to be expected?

Exercise 8.11

Set the data-generating process to be a 3rd-order polynomial and set limits of the the predictor variable to [-3,3]. Analyze the data using a 2nd-order polynomial model.

Explore the limit of \(N_d \rightarrow \infty\) by setting \(N_d = 500\) or so. Will the OLS values of the model parameters and the sample variance approach the (true) values for some of the parameters?