17.3. Visualizations#

Javascript visualizations of MCMC#

There are excellent javascript visualizations of MCMC sampling available on the web. A particularly effective set of interactive demos was created by Chi Feng, available at https://chi-feng.github.io/mcmc-demo/ These demos range from random walk Metropolis-Hastings (MH) to Adaptive MH to Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) to No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) to Metropolis-adjusted Langevin Algorithm (MALA) to Hesian-HMC (H2MC), to Stein Variational Gradient Descent (SVGD) to Nested Sampling with RadFriends (RadFriends-NS). We will only consider a subset of these samplers in this book, but the reader is encouraged to explore further.

An accessible introduction to MCMC with simplified versions of Feng’s visualization by Richard McElreath. Let’s look at the first part of his blog entry at http://elevanth.org/blog/2017/11/28/build-a-better-markov-chain/. (Overall this blog promotes Hamiltonian Monte Caro; we return to the HMC visualization in a later section.)

When looking at the visualizations, remember the basic structure of the MH algorithm:

Make a random proposal for new parameter values.

Accept or reject the proposal based on a Metropolis criterion.

Exploring the MH simulation from McElreath#

Here are some comments and observations on the basic MH simulation from the McElreath blog.

The target distribution is a two-dimensional Gaussian (just the product of two one-dimensional Gaussians).

Checkpoint question

Is the distribution correlated? How do you know from the simulation?

Answer

The distribution is uncorrelated. The accumulated joint posterior has horizontally oriented ellipses (circles if the scales are equal). They would be slanted if there were correlations.

An uncolored arrow indicates a proposal, which is accepted (green) or rejected (red).

Notice that the direction and the length of the proposal arrow varies and are, in fact, chosen randomly from a distribution. The direction is sampled uniformly.

The MH MCMC seems to do ok on sampling such a simple distribution, as indicated by how well the projected posteriors get filled in.

But it is diffusing, i.e., a random walk, which is not so efficient. A more complicated shape can cause problems:

MH can spend a lot of time exploring over and over again the same regions;

if not specially tuned, many proposals can be rejected (red arrows).

Try the donut shape, which is much trickier.

Notice that the projected one-dimensional posteriors don’t seem to be so complex, but this is a difficult topology.

Is this shape realistic? The claim is that when there are many parameters (a high-dimensional space), this is analogous to a common target distribution. The probability mass concentrates in this shape.

Note on donuts in high dimensions

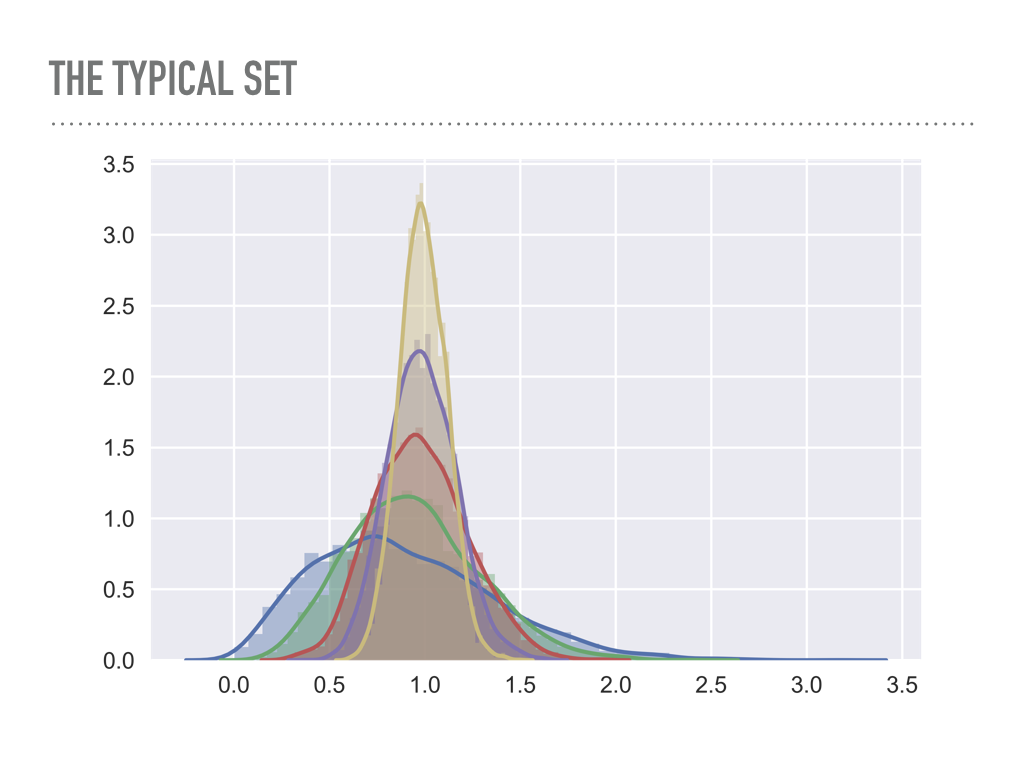

Look at the average radius of points sampled from multivariate Gaussians as a function of the dimension.

blue is one dimensional, green is two dimensional, … , yellow is six dimensional.

Imagine yellow as a 6-dimensional shell \(\Lra\) the analog is a two-dimensional donut.

Problems: we are constantly looking for the right step size, which is big enough to explore the space, but small enough to not get rejected too often.

High dimensions is a big space! It is hard to stay in a region of high probability while also exploring enough of the full space (in a reasonable time).

Now take a look at the Feng site and try the different distributions available.

The banana distribution \(\Lra\) difficult to sample.

If the distribution multimodal \(\Lra\) very, very tough to sample effectively.

Try adjusting the proposal \(\sigma\) (there is a Gaussian proposal with variance \(\sigma^2\)) \(\Lra\) try this on donut: to get a reasonable rate of green arrows you need excellent step size tuning.

Back to the McElreath page. What is the answer to better sampling? His claim: “Better living through physics”

For McElreath, this means to use Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC).

Later we’ll come back to HMC but stick with MH for now.

Challenges in MCMC sampling#

We have seen that these are problematic PDFs:

Correlated distributions that are very narrow in certain directions (scaled parameters needed).

Donut or banana shapes (very low acceptance ratios).

Multimodal distributions (might easily get stuck in local region of high probability and completely miss other regions).