1. Invitation to inductive inference#

1.1. Demolition derbies, cows, and crocodiles#

This is a book about how to glean scientific results from data. The collection of data is often a heroic task: physicists build huge accelerators, launch telescopes into space, and spend years monitoring bodies of matter underground to detect sub-atomic messengers from within our galaxy and beyond. But without inference all that data is just a list of numbers.

Inference is “the act or process of reaching a conclusion about something from known facts or evidence.” Theoretical physicists have traditionally trained themselves to become experts at deductive inference. They posit a theory of nature, or perhaps, less ambitiously, some phenomenon within nature, and deduce the effects that will follow from that cause. Mathematical proofs are the Platonic ideal of deductive reasoning. And, we often teach our students that the practice of science lies in deducing predictions from theories and then doing experiments that falsify those predictions.

With apologies to Karl Popper, this seems a deeply unsatisfying way to practice science. After all the falsifying is done, what has one established? Is this a scientific version of a demolition derby, wherein the theory least beaten up by all those comparisons with data is declared the bloody but unbowed winner?

Therefore this book focuses on inductive inference. And specifically inductive inference to the best explanation. Here best may involve determining the parameters of a particular model, or choosing between different competing models, or combining the predictions of these models. But instead of the deductive inference of the mathematicians–lovely though that may be–here we are in the realm of what Polya calls “plausible reasoning”. Instead of an ironclad syllogism: “All cows eat grass, Betty is a cow, therefore Betty eats grass”, we deal in logic that takes us from data to a model of a reality: “Betty eats grass, therefore it is more likely that Betty is a cow than that she is a crocodile”.

But how much more likely? Our physicist training cries out for us to quantify the strength of this bovine inference. And, to update the quantification if we acquire more data, for instance, that Betty also says “Moo”.

Bayes’ theorem provides us with a mathematical identity (deductively inferred!) that tells us how to do the latter: how to update our inferences as more data is acquired. But to do this we must couch our inference of Betty’s species identity in the language of probability. You might think this a bug, but we will argue throughout this book that it’s a feature, because it means that our inferences are then subject to the laws of probability. And these too are mathematical rules that tell you quantitatively how additional assumptions you may make along your path from data to inference affect your final conclusion.

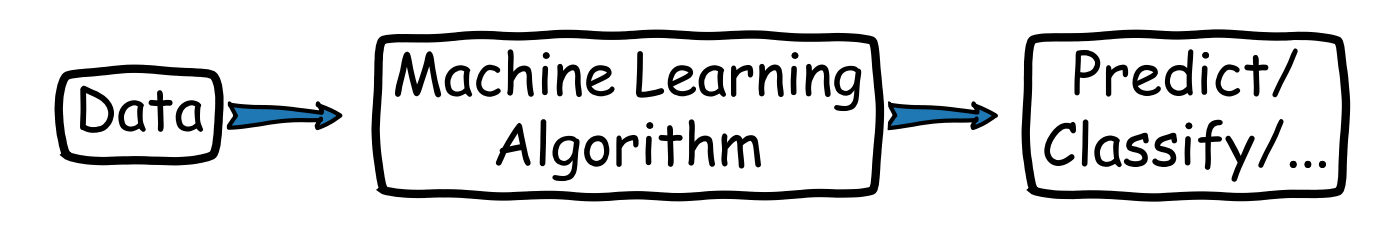

The basic process of inference is employed also in the field of machine learning. Here, the learning part might take place when confronting a large set of data with a machine learning algorithm, and the specific aim might be tasks such as classification or clusterization or emulation. We aim in this book to bring a particularly Bayesian perspective to our consideration of machine learning.

Fig. 1.1 Machine learning can also be seen as an inference process.#

On the one hand, we will study statistical inference methods for learning from data as needed for scientific applications. Simultaneously this statistical foundation will provide a deeper understanding (and probabilistic interpretation) of machine learning algorithms. This will enable statistical learning.

1.2. Polya and Jaynes#

Polya and plausible inference

George Polya was a leading mathematician in the mid-twentieth century. In his two-volume book on “Mathematics and Plausible Reasoning” from 1954 [Pol54a, Pol54b], Polya wrote:

“A mathematical proof is demonstrative reasoning but the inductive evidence of the physicist, the circumstantial evidence of the lawyer, the documentary evidence of the historian and the statistical evidence of the economist all belong to plausible reasoning.”

Polya contrasts a standard deductive inference involving statements A and B (an Aristotelian syllogism):

If A implies B, and A is true, then B is true

with an inductive inference:

If A implies B, and B is true, then A is more credible.

He considers qualitative patterns of plausible inference as a guide toward mathematical discovery; he wrote: “Mathematics presented with rigor is a systematic deductive science but mathematics in the making is an experimental inductive science”.

However, as physicists we seek quantitative inferences.

In particular, physicists need ways to:

quantify the strength of inductive inferences;

update that quantification as new data is acquired.

This is what Bayesian inference will do for us!

Edwin Jaynes and plausible reasoning

Edwin Jaynes, in his influential How does the brain do plausible reasoning? [Jay88], wrote:

“One of the most familiar facts of our experience is this: that there is such a thing as common sense, which enables us to do plausible reasoning in a fairly consistent way. People who have the same background of experience and the same amount of information about a proposition come to pretty much the same conclusions as to its plausibility. No jury has ever reached a verdict on the basis of pure deductive reasoning. Therefore the human brain must contain some fairly definite mechanism for plausible reasoning, undoubtedly much more complex than that required for deductive reasoning. But in order for this to be possible, there must exist consistent rules for carrying out plausible reasoning, in terms of operations so definite that they can be programmed on the computing machine which is the human brain.”

Jaynes went on to show that these “consistent rules” are just the axiomatic rules of Bayesian probability theory supplemented by Laplace’s principle of indifference and, its generalization, Shannon’s principle of maximum entropy. This key observation implies that we can define an extended logic such that a computer can be programmed to “reason”, or rather to update probabilities based on data. Given some very minimal desiderata, the rules of Bayesian probability are the only ones which conform to what, intuitively, we recognize as rationality. Such probability update rules can be used recursively to impute causal relationships between observations. That is, a machine can be programmed to “learn”.